Unilever shifts focus to African suppliers as currency market pressures intensify

Amidst pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, rising costs and increasing currency volatility, Unilever is shifting its focus to African suppliers. By sourcing more locally, the multinational hopes to improve the self-sufficiency of its operations on the African continent. While the main reason for this move is to manage currency risks, local farmers are also benefiting.

The 76-year-old farmer Busari Kasali used to be afraid that his cassava – an important crop in his native Nigeria – would perish before it got to market. Today, his main concern is meeting Unilever’s growing demand. According to experts, the company is a blessing for farmers and processors in various parts of Africa. In Kasali’s case, his income from cassava has almost tripled in the past two years: “We can now plant as much as we want. We know that we will be able to sell it.”

Like most companies, the consumer packaged goods giant has struggled with the rising costs of energy and raw material over the past two years. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated the supply chain disruptions and production issues that were triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The group was hit by net material inflation totalling more than €4 billion last year, and raw material prices are expected to continue to rise for the foreseeable future.

Exchange rate fluctuations

Growing debt in many African countries has put pressure on foreign reserves and led to exchange rate fluctuations that make it harder and more expensive to import raw materials. “More than 95% of the brands we sell to African consumers are made in African factories,” says Reginaldo Ecclissato, Chief Business Operations and Supply Chain Officer at Unilever.

Until recently, Unilever sourced less than a third of the necessary raw materials within Africa, but more than two-thirds of the ingredients needed for Unilever products sold in African countries now come from the continent itself. In particular, rather than importing sorbitol and spices from India and China as before, the company is increasingly sourcing them from suppliers in nations such as South Africa and Nigeria.

Unilever is not alone in opting for this strategy. According to Tedd George, a supply chain consultant specializing in Africa, companies such as Nestlé and Danone are also intensifying their focus on Africa. This is partly due to the fast-growing consumer market, and also in an attempt to reduce their dependence on China and avoid a repeat of the inertia caused by Beijing’s strict lockdowns during the pandemic, George says.

Accelerated by the pandemic

Although Unilever actually began sourcing more from within Africa around four years ago, the shift was accelerated by the pandemic, Ecclissato states. In South Africa, for example, a network of small farmers has been set up to grow coriander and chili peppers for the Robertsons local spice brands, Rajah curry blends and Knorrox stock cubes. Meanwhile in Nigeria, where between 10,000 and 14,000 tons of CloseUp and Pepsodent toothpaste are produced annually, Unilever is stepping up local sourcing of sorbitol, an ingredient previously imported from China that can be extracted from cassava.

Yemisi Iranloye, whose company Psaltry International processes cassava from around 10,000 farmers including Busari Kasali, is capitalizing on this shift. She started supplying sorbitol to Unilever late last year and the multinational now takes approximately 70% of Iranloye’s total sorbitol production, accounting for about 40% of Psaltry’s total sales.

Dollar shortages and currency fluctuations

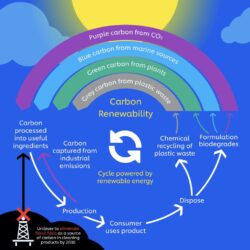

According to Unilever’s Ecclissato, local sourcing contributes to closer collaboration with suppliers, transportation savings and a smaller carbon footprint. Another key advantage is that less foreign exchange is needed to pay for imports. For a company like Unilever, which generated US$153 million in sales in Nigeria alone in 2021, the costs associated with securing the necessary dollars can soon mount up.

Iranloye, who also supplies to Nestlé and Danone, believes that the desire to hedge against dollar shortages and local currency fluctuations is fuelling demand among all her customers, and she expects Psaltry’s sales to more than double this year. “This trend is also improving life for people on this continent, especially farmers,” she says.

However, Africa’s ability to produce raw materials – especially agricultural commodities – may be a limiting factor, at least in the short term. Iranloye recently upgraded her cassava processing plant to meet the growing demand from Unilever and others, but it is currently running at only about 60% of its capacity. “We still don’t have enough cassava,” she states. ‘Raw materials are a challenge. The farmers need to have good access to financing.”

Source: Reuters